The Swedish Club

1920 Dexter Avenue N, Seattle, WA 98109

Built 1960

The content below is from a 2019 Seattle Landmark Nomination form by Larry Johnson and Susan Boyle

History

By 1910, immigration had brought the number of foreign-born Scandinavians to approximately 19,046, about 31 percent of the foreign-born population. During these early years Scandinavians established both fraternal organizations and churches where immigrants could find mutual support and continue cultural traditions. These organizations and churches originally consisted exclusively of immigrants of individual countries of origin. Later, as Scandinavian immigrants were successfully integrated into Seattle’s general population, they used their wealth to reinforce their identities and cultural traditions. In the mid-twentieth century the Scandinavian community came into its own, prosperity-wise, and began to celebrate its identity. Churches and institutional buildings replaced their more provisional predecessors with structures that generally reflected more conservative Modernist design traditions. Church construction and expansion were especially marked during this time, albeit uneven in quality.

The idea of a social club for Swedish immigrants living in Seattle originated in 1892 at the Stockholm Hotel, which was owned by Swedish Honorary Consul Andrew Chilborg, at the southeastern corner of First Avenue and Blanchard Street. At that time the northern part of the city housed many northern European immigrants. In the 1890s, the Stockholm Hotel provided not only housing accommodations for young male Swedish Immigrants, but also a restaurant and an office for Svenska Pressen, Seattle’s Swedish-language newspaper. At that time there were few places where young single men could meet young women, so they came up with the idea of forming a club where they could socialize.

In August 1892, 30 young men met at the new Masonic Temple at Pike Street and Second Avenue. There was a general agreement that a social club for Swedes was needed, and committees were formed to start the club. In less than a year the club had grown exponentially, and the idea of a social club to meet young women was soon expanded to include families. Women were welcome to come to social events, but meetings were exclusively for men. Initially the club rented rooms at the Carpenter’s Union Hall, and for a small apartment at Seventh Avenue and Columbia Street, and in the basement of the first Ranke Building at Pike Street and Fifth Avenue. Over the years the Swedish Club sponsored many traditional Swedish events.

Discussions concerning the club building its own clubhouse began in 1901. Nels B. Nelson, one of the founders of the Frederick & Nelson department store chain and member of the club, had purchased a double lot on the corner of Eighth Avenue and Olive Street (now the Hyatt Hotel) for $6,000 and sold the mid-block lot to the club for $3,000. Club member and contractor, Otto Roseleaf, prepared the construction drawings for the Swedish Club’s first building and constructed the modest wood-frame clubhouse that opened in 1902.

After World War II, progressive members of the club began considering constructing a new, larger club building. Club president Andy Berglund had high aspirations and coined a slogan “Membership of 1000 and a new building”, initiating a campaign to realize his vision. The campaign increased the number of members from 150 to 500. The club also explored purchasing property on the northeastern corner of Eighth Avenue and University Street (now Freeway Park), but members deemed it too expensive. In August 1951, the club’s leadership invited other Swedish organizations and societies in Seattle to participate in their discussions about forming a joint building association to build a new building. After September 1951, the Swedish Club’s building committee started working jointly with other organizations. Two lots at Second Avenue and Broad Street were bought in February 1952. However, financing a joint venture proved more difficult than originally anticipated. The total cost of the lots and construction of the building were anticipated to cost $900,000. After repeated attempts the Swedish Community Building Association dissolved and the board of directors of the Swedish Club decided to move forward on a smaller-scale building without partners. However, the Swedish Club still owned the two lots at Second Avenue and Broad Street. The club considered the site too valuable for the smaller building they now envisioned, so they sold the lots in early 1957 for a profit.

A few weeks after the sale of the old property, the club was offered a new site at 1920 Dexter Avenue N by one of the members and moved to purchase it. The old club building at Eighth Avenue was later sold and demolished and served as a parking lot for several years. The new property was less expensive and also had the advantage of adequate space for parking and a great view over Lake Union. The club now engaged architects Steinhart, Theriault & Anderson to design their new building. Einar V. Anderson, a member of the Swedish Club, was the firm principal in charge of the design, signing all the original drawings. The resulting design was inspired by Minoru Yamasaki’s Reynolds Aluminum Building (1959) in Southfield, Michigan, sharing the same exterior aluminum sunscreen composed of interlocking aluminum rings developed by the Reynolds Aluminum Company The groundbreaking ceremony was held on November 28, 1959.

The new Swedish Club building officially opened in April 1961, featuring a central atrium and an upper-floor restaurant. Final cost for the building was around $500,000, which came wholly from the organization’s own funds, sale of bonds to members and others, and from donations. Members also did all the painting work and installed the exterior aluminum sunscreen. As the organization approached 100 years of age in the 1990s, however, it was forced to curtail some operations and begin a long period of deferred maintenance decisions. The once-popular restaurant was closed and rented to an outside caterer for additional income. A corridor was inserted into the club’s private dining room/boardroom to allow the catering business direct access to the elevator, with the caterer using the southern auditorium entrance for loading rather than the original northern loading area. The main offices near the entrance were also rented to a related organization, and the building was marketed to individuals and organizations with no cultural connections to the club. Non-members were also allowed access to the facility’s meeting rooms and auditorium on a rental basis and were invited to enjoy the club’s bar area for a small fee. Although these actions allowed the club to barely survive financially, cumulatively they weakened the sense of community.

In spite of concerted efforts to revive the Swedish Club, by 2005 the organization had reached an impasse. Without clear direction or purpose, other than continuing the monthly popular Swedish Pancake Breakfast offering, membership had dwindled to around 550 members who paid annual dues of $85 for minimal benefits. Many, including the club’s executive director and several of the board members, thought its failure and liquidation of the club’s assets was inevitable. Several club members—including Karl Larsson, Brandon Benson, and Kristine Leander—rejected this premature death certificate and in fall of 2005, began meeting in order to preserve and create a future for the club. Today, the Swedish Club’s membership appears to be stable, with approximately 1,100 members. The club publishes a monthly newsletter and has an active website describing events. The Club’s Swedish Pancake Breakfast has become a Seattle community tradition, usually serving approximately 400 people the first Sunday of every month. Its facilities are currently used by many smaller Scandinavian and non-Scandinavian organizations and clubs, and also operates as an entertainment and event venue.

The Building and Site

The Swedish Club building, built in 1960, is situated on a 0.92‐acre foot, L‐shaped site at the southeast corner of the intersection of Dexter Avenue N and Newton Street. The site is on the east side of Queen Anne Hill and the east side of Dexter Avenue N, approximately halfway between the South Lake Union area and Fremont. At this location the hill slopes steeply downward to the east. Newton Street stops one block short of extending down to Westlake Avenue N, three blocks away.

The structure consists of reinforced concrete with an 8”‐thick foundation and first floor walls, 8”‐wide pumice block walls, 4”‐thick floor slabs, and 14” piers and perimeter pilasters. Upper floors are framed with steel wide flange beams and columns, and the roof has steel decking.

The overall structure is made up of six 15’‐wide bays along the north and south and eight 10’‐wide bays along the east and west. Beyond the resulting 90’‐wide by 80’‐deep envelope there are 5.5’‐deep walkways or cantilevered balconies and roof extensions on the north, south and east. The exterior is wrapped on these three sides by 30’‐tall decorative aluminum screening.

Because of the building’s size, scale and visibility, all facades appear primary, although the south and west facades are clearly more visible. The appearance of the facades varies, due to the topography and the architectural composition. This results in what appears to be a two‐story primary west facade, facing onto Dexter Avenue N, and three story facades on the north, south, and east. In response to internal functions and the view opportunities, the western half of the building is largely solid, with few penetrations but for doorways, while the eastern half is largely transparent due to full‐height windows on the upper floors and a wide band of east‐facing windows on the first floor. Wall infill consists of solid material – scored concrete and the concrete block treated with cement plaster cladding with an “oversize aggregate” or “marblecrete” finish as cited on the original elevations—or fenestration.

The main entry is sheltered below a deep canopy made up by an angled and shed roof frame of steel bents and steel decking. Designed by Steinhart Theriault & Anderson, the canopy was added to the original flush front facade in 1972. The canopy is supported by paired square steel tubes that extend above the canopy roof to serve as flag poles. The three pairs of entry doors—also painted blue—are fitted with custom cast bronze and terrazzo pulls that depict the traditional Swedish five‐pointed crown. The flat roof edge is finished with a deep light gray aluminum metal cap. A granite dedication plaque is set into the concrete block near the south end of the west facade, noting the construction date and the design architects. The orignal building had a simple sign reading “Swedish House” on the west facade that was apparently removed when the canopy was installed. The upper two levels of south, east and north facades read in part as curtainwalls because of exterior screens, which are hung from the outer edges of the roof and cantilevered floor slabs. Exterior stairs accessing upper floors are fitted between the building’s perimeter walls and the screens on the building’s north and south sides, while solid soffits extend below the slabs to create strong horizontal bands at three levels, which serve to protect walkways below and the first floor entry on the south side. Hung on the outer surface of the sunscreen there is a circular emblem and a solid rectangular sign, reading “The Swedish Club” along with the crown symbol in blue and yellow—the colors of the Swedish flag. The exterior screening may be the most expressive component of the building.

Behind the screens there are full‐height aluminum frame windows that are placed between the concrete piers, with tripartite vertical division and a lower hopper section. Where there are no windows, on the western half of the north and south facades, the exterior screening shields the painted wall infill and adds surface texture rather than actual sun screening. The original screens enclosed all of the glazed walls north and south walls, while only the lower portion of the east walls, but the upper two‐thirds of the screening was removed on the north and south by the Swedish Club in an effort to provide more expansive views from the building’s upper floors. The remaining screening, 42 inches height, acts as a railing infill below a horizontal aluminum flat bar. In these areas only the vertical bars remain, three at each bay space, to give a crisp vertical rhythm to the facades.

Symbolic details include some original teak finishes and the exterior color palette of blue and white, which was inspired by the Swedish flag. The custom‐fabricated entry door pulls were designed by the orignal architect, Einar Anderson, who donated them in memory of his father. Shown in the original drawings as having three points the design recalls the national Swedish emblem, Tre Kronor (three coronets).3 The final installed pulls depict a five‐pointed crown in bronze with terrazzo infill.

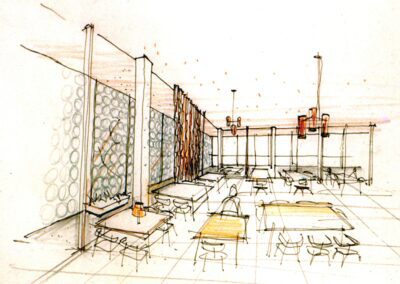

The building contains three floors and a small basement, which is set below the northeast section and contains mechanical rooms and a small storage/workshop at the eastern end. Floor heights are tall throughout, with 11’ from the basement to first floor, 14’ from the basement to first floor and 13’ each at the upper two floors. The monumental stair is an open Modern style element set along a north wall of 2‐1/4” red brick, where it leads up to the upper floor. The 5.5’‐wide stair is supported by steel rods from the ceiling, and is made up by open risers, treads of steel pans with concrete terrazzo infill, and teak handrails. The gallery at the third floor overlooking the space below is detailed with the same vertical rods, which serve as screening and guardrail. The rail around the opening to the lower stair is similar. The gallery leads across the east side of the upper foyer space to a prominent cocktail lounge at the building’s southeast corner and a large dining room to the north of it. Both of these primary social spaces once served as a restaurant in the building. They both provide expansive views eastward of Capitol Hill and Lake Union and other parts of the city to the north and south. The dining room is finished with non‐original carpet and acoustic fabric ceilings, and wall paneling. Non‐original small crystal chandeliers are suspended from its ceiling, while the lounge space has Modern era but non‐ original light fixtures. A hallway leads westward to enclosed stairs accessing the main floor, restrooms, a mechanical room, and the elevator located near the building’s southwestern corner. A large commercial kitchen and smaller catering kitchen area is located on the building’s northern side, and an enclosed private dining room on the west.

The Architects: Arden Croco Steinhart (1906-1994), Robert Dennis Theriault (1922-2005), Einar V. Anderson (1925-1970)

The Seattle architectural firm of Steinhart, Theriault & Anderson designed the Swedish Club building at 1920 Dexter Avenue N in 1959. The Swedish Club building can be classified stylistically—by its massing, scale, and use of an exterior brise soleil—as being in the Modern/International Style, expressive of the New Formalism, and classified by its materials as loosely derived from contemporary Northern European precedents.

The firm’s senior partner, Arden Croco Steinhart (1906-1994), was born on November 21, 1906 in Bucoda, Washington. He earned his architectural degree at the University of Washington in 1929. Between 1930 and 1939 he worked as a lathe foreman in a local lumber mill where his father was a superintendent. Between 1937 and 1942, Steinhart worked as a draftsman for William Jones and Roy Chester Stanley (1886-1956) at the Seattle architectural firm of Jones & Stanley. In 1951, Steinhart became a third partner in the firm, now known as Jones, Stanley & Steinhart, Architects Robert Dennis Theriault (1922-2005) joined Steinhart & Stanley in 1953 (Jones had retired the previous year), forming the partnership of Steinhart, Stanley & Theriault.

Robert Dennis Theriault was born in Tacoma on May 28, 1922 and attended McCarver Common School, graduating from Stadium High School. In 1945 his family moved to Seattle so that he could attend the University of Washington on the GI Bill. Theriault received his degree in Architecture in June 1950. Theriault was then employed by engineer E.G. Putnam, and by architect Alfred F. Simpson, as an architectural and structural designer, drafter, renderer, and in 1950-1952 as a job supervisor.

Einar V. Anderson (1925-1970) became the fourth partner in 1955. Stanley left the firm in 1959. Anderson was the partner who primarily was responsible for the design of the Swedish Club and signed all the construction documents. Einar Vincent Anderson was born in Seattle on January 22, 1925, the third son of Swedish immigrants Emil W. and Hannah B. (Arvidsson) Anderson. Einar grew up in Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood, and graduated in 1942 from Lincoln High School. At that time he was considered a talented illustrator and cartoonist, expressing an interest in becoming a commercial artist. In 1946, he enrolled in the University of Washington, graduating in 1951 with a Bachelor of Architecture (Tau Sigma Delta). He was a second-generation Swede and also a member of the Swedish Club. He died prematurely at age 45 in 1970. After Anderson’s death, the firm was reorganized as Steinhart, Theriault & Associates. In 1985 the firm added a new partner, John Courage, under the name of Steinhart Theriault & Courage.

Steinhart, Theriault & Anderson designed a number of projects in the Seattle area in the 1950s and 1960s. The firm specialized in low-scale buildings in the Northwest Modern style. The firm’s most notable designs were their own architectural office building, the Swedish Club, Normandy Park Community Center in Normandy Park Cove Building, and Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church.