The Space Needle

219 Fourth Avenue North, Seattle, WA 98109

Built 1962

The content below is from a 1998 Seattle Landmark Nomination form.

History

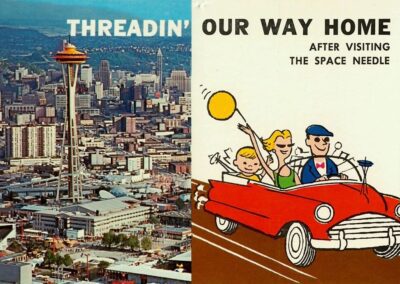

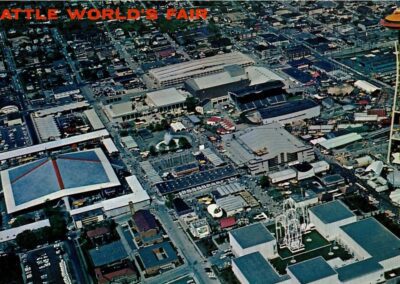

The Space Needle was an important component of the 1962 Seattle Century Twenty-One Exposition. The 74 acre fair site is located approximately one mile north of the City’s downtown retail core and adjacent to the Denny Regrade and South Queen Anne neighborhoods. The site is bounded by Mercer Street and Denny Way, and First and Fifth Avenues. Portions of the fair site make up the current Seattle Center.

The Fair was conceived of as a “Gateway-to-the-Pacific” trade festival, and funding for it was provided initially by a $7.5 million public bond in 1957. World Fair status was achieved after additional local economic investment in the site and federal appropriation of $9 million for the purpose of a United States science exhibit. Official approval was granted in April of 1960 by the Bureau of International Expositions.

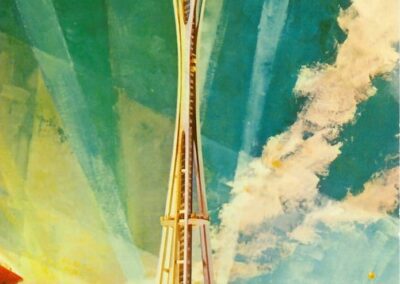

The idea of a significant architectural structure to serve as a symbol for the 1962 World’s Fair was not a unique one. In this sense, the Space Needle can be seen in the historic context of landmark pavilions and urban towers which have served as symbols and monuments throughout the world. In its specific context, however, the Space Needle marks a point in the history of the City of Seattle and represents American aspirations towards technological prowess.

Influenced by existing structures in Europe—such as the 1956 Stuttgart Television Tower and the 1958 Belgian Atomium—Edward Carlson, President of the nonprofit World’s Fair Corporation, posed the challenge to the coordinators of the World’s Fair to create a similar icon in Seattle. Their task was to “submit an idea for a spectacular structure to symbolize and dramatize the Century 21 Exposition and to serve as a permanent, profit-making attraction for the City of Seattle.”

Architect and Planner Paul Thiry was appointed the principal designer of the grounds in 1957. His design unified the pedestrian precinct of approximately 30 city blocks and ordered the spaces into “the five worlds of Century 21” which were organized through a series of pathways, streets, and plazas, known as “the Boulevards of the World.” In keeping with the theme of Century 21, the exposition grounds were linked to the downtown area via a new mode of transportation, the Monorail, an elevated light-rail system.

Unlike many previous world fairs, the buildings on the Seattle site were permanent, and were later restructured to become part of the Seattle Center complex. The long-range vision of city planners allowed for money to be appropriated for this purpose. The fairground structures were designed at the height of Modernism, and this was reflected in their original designs. In a commercial example of an immense clear span space, Thiry’s use of concrete for the Coliseum represents an innovative attitude towards this material and its design application.

Due to planning and the economic provisions arranged before the inception of the World’s Fair, the site of the exposition became a permanent, multi-purpose complex for the citizens of Seattle. In the site’s Master Plan Paul Thiry and landscape architect Richard Haag developed a scheme of connecting covered passageways and tree-lined paths to guide visitors to the various areas of the site and frame vistas of the surrounding city and horizon. Internal zones of the Seattle Center grounds were treated individually.

Paul Thiry envisioned the eventual removal of the fair’s periphery walls to make the Seattle Center visually more open to the public. Some of these features of Thiry’s plan have been implemented over the past 35 years. Much of what has been executed on the grounds is in the form of landscaping and permanent paving, which has helped to make the site usable and enjoyable throughout all months. Expansion and addition of performance and theater spaces, and exhibit halls have occurred in the recent decade.

As a convenient, large location, the Seattle Center has served and continues to be used for major public events. With cultural facilities—such as the Opera House, the Children’s Theater, the Bagley Wright Theater, and the Pacific Northwest Ballet headquarters—the Coliseum/Key Arena, and the Science Center forming the complex, it is utilized constantly by both residents and visitors to the Puget Sound region.

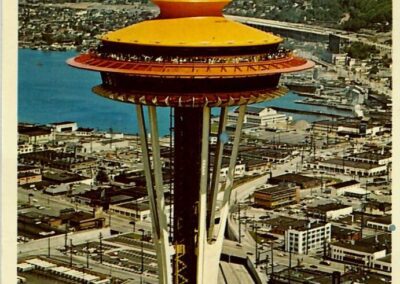

Anchoring the southeast corner of the Century 21 exposition site, the Space Needle embodied the beliefs of the time. Its futuristic form and height engendered awe, and it was immediately seized as the new emblem for Seattle. The building is a pervasive presence within the city and is used as a geographical marker by visitors and Seattlelites. Because it is so clearly identifiable in its concept, form, and materials, the Needle is also a visual reminder of the optimism which accompanied technology in the 1960s.

The Space Needle provides encompassing views of the city for visitors to its upper levels. Its exterior has been utilized continuously for display and special events that affect the city or the region, such as holidays, sporting events, or fireworks celebrations.

The Site

The site of the Space Needle is a 128’ by 120’ parcel located near the southeast corner of the Seattle Center, and the intersection of Fifth Avenue North and Broad Street.

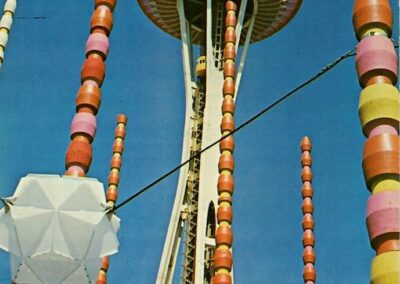

During the Seattle World’s Fair this site acted as a gateway to the southern entrance of the fair grounds and the Monorail terminal. The “gayway” amusement area was created near this location, along with exhibit halls such as the Bell System Pavilion and the Wood Products Display Hall.

Because of its prominent location, the Space Needle affords views of and can be seen from many locations and neighborhoods in Seattle including Capitol, First, and Queen Anne Hills; the downtown, Denny Regrade, Wallingford, and West Seattle; and from ships in Elliott Bay.

Fair organizers Jim Douglas and Edward Carlson had approached architects John Graham and Company to conceive of some preliminary designs. Designers from Graham’s office who were initially involved in the conceptual stage of development included Art Edwards, John Ridley, and Victor Steinbrueck.

Some of the preliminary designs can be categorized as elaborations upon the “tethered balloon” or the “spiked flying saucer” concept. It was Ridley’s idea of the cruciform shaft and disk structure that focused the design efforts of the entire team for the rest of the schematic stage. Further development of the tripod structural system that was to evolve into the familiar image of the Needle is attributable to Victor Steinbrueck.

The Space Needle, as originally conceived, embodies in its form and construction that era’s belief in commerce, technology, and progress. Three pairs of slender steel legs curve inwards from a 102’ diameter base to the 373’ “waist” level and flair out into an hourglass form to hold a disc shaped structure at the top, which is comprised of a revolving restaurant, a mezzanine, and an observation deck. The top 50 feet of the structure was a flame of natural gas, which was ignited from a tripod of stainless steel. (The flame was subsequently dismantled and replaced by an aircraft warning beacon.)

Visitors to the top of the Needle ride one of three 29 passenger elevators, which travel at speeds of up to 800 feet a minute. One of these elevators is utilized also to service the restaurants and for staff. In addition to mechanical and electrical equipment, the internal core of the structure contains two separate weaving staircases of 832 steps apiece. All three elevators were replaced in 1993; the new elevators matched the capsule form of the original design.

Many of the construction techniques used in building the Space Needle were revolutionary and set construction industry records. The structure’s foundation consisted of a 30 foot deep, Y-shaped pit, which was filled with 2,819 cubic yards of concrete and 250 tons of reinforcing steel. Laying of the foundation was performed in under 12 hours and set the west coast record for the largest continuous concrete pour. The entire structure was realized in only 400 days, from design conception to completion of construction.

An alteration on the grade level of the Space Needle was made immediately after the World’s Fair in October of 1962. This consisted of a glass and aluminum-framed enclosure fabricated in 4’ sections to provide shelter to waiting patrons. Architect John Graham envisioned that this would be a semi-permanent, seasonal structure, and designed it to be readily dismantled for the warm summer months. This 3,000 square foot, heated space was enclosed, and evolved into the current carpeted and climate-controlled base structure which currently houses retail facilities and a reception lounge for restaurant customers.

Alterations that occurred at the Plaza (base) level in 1966 included a new metal canopy, designed to align with the window mullions of the glazed walls below. New terrazzo flooring was added, and concrete planters and new sections of landscape walls were structured to match existing portions along the perimeter of the property. Drawings dated May 9, 1977, indicate internal modifications to the base facility.

The steel and glass structure at the base of the Needle’s legs currently serves reception, and retail functions. Exterior glazing along the southeastern and southwestern wings, and also along the southern facade, is treated with a film that is mirrored from the exterior, and darkened on the interior. The exterior appearance is reflective rather than transparent. Glazing in the northern wing of the base structure is clear and remains untreated.

An additional dining and conference facility was designed for the 100’ level in 1978. It consists of three wings that cantilever from the core, each projecting between the legs and characterized by bands of dark tinted windows. A center service core and lobby were accessed via the existing elevators.

The addition was constructed in 1981 and opened in 1982. It was designed to function as a single large space, or to divide into three units for smaller parties, each with a 180 degree view of the city, mountains or the Puget Sound. Each dining area corresponds with the retail wings at the base level. The internal spaces areas around the core provide for services, such as a kitchen and bathrooms, as well as a bar in the northwest portion of the space.

The Architects, John Graham, Jr. (1908-1991) and Victor Steinbrueck (1911-1985)

A Seattle native, John Graham Jr. studied architecture at the University of Washington before transferring to Yale where he received his degree in 1931. Prior to 1962, Architect John Graham Jr. was perhaps best known for the design of Northgate Mall. This mall was the first of its kind in the United States, and would later develop as a typological element in the suburban landscape. The firm of John Graham Jr. and Company specialized in large-scale, fast-track jobs.

Graham’s reputation for correctly assessing a project’s schedule, budget and feasibility had earned him the title “a businessman’s architect.” Because of his reputation, organizers of the 1962 World’s Fair hired Graham to design the Space Needle.

Having been assigned the challenge to design a visionary piece of architecture to embody the spirit of the theme “Century 21,” John Graham Jr. conceived of the form that would later become more highly developed and refined by Victor Steinbrueck, a member of the original design team of John Graham and Company.

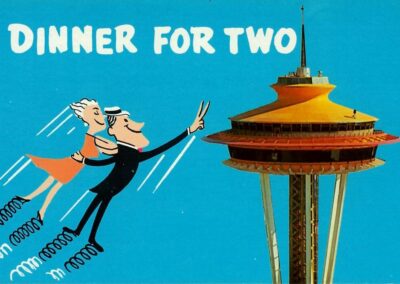

In addition to this, investors were interested in securing in the Space Needle an attraction for the City of Seattle that would become a permanent commercial enterprise. Graham, who had utilized the idea of a revolving restaurant previously in Honolulu, developed this idea further by combining these facilities with an observation deck and lounge.

While the initial conceptualization of the form of the Space Needle can be ascribed to John Graham Jr., it is believed that Victor Steinbrueck and other design team members from Graham’s firm were responsible for the formal design development.

Born in Mandan, North Dakota in 1911, Steinbrueck graduated with an architecture degree from the University of Washington in 1935. As a consultant to John Graham and Company, Steinbrueck played a key role in the Space Needle’s design.

Steinbrueck was also a historic preservation activist, and was known for his Pioneer Square and Pike Place Market preservation efforts.