McAdoo House

The content below is from a 2023 Bothell Register of Historic Landmarks Nomination Form prepared by Penelope Cottrell-Crawford and Tom Heuser of Willamette Cultural Resources Associates, Ltd. The McAdoo House property was nominated by the Bothell Landmark Preservation Board at its meeting on September 26, 2023. However, the property has not yet been designated and officially listed on the Bothell Register of Historic Landmarks. Designation should take place sometime in 2024.

History

The McAdoo House was built in 1958 and designed by Benjamin Franklin McAdoo Jr. (1920–1981), built by Edwin L. Dahlbeck (1912–1992) with the cooperation of landscape architects Edward M. Watanabe (1920–2018) and Fred Wray (unknown). Contextually, the house relates to the social history of civil rights activism across the US as embodied in the life story of Benjamin McAdoo Jr., who led a career of architectural innovation and civil rights activism, and who was the first Black architect registered in the state of Washington.

McAdoo designed the subject residence as a private home for himself and his family in the middle of his distinguished career as an outstanding and prolific architect who fought tirelessly for civil rights and housing access.

Benjamin Franklin McAdoo Jr. (McAdoo) was born in Pasadena, California on October 29, 1920. While attending school through the 1930s, McAdoo assisted his father’s tree hauling and hardwood flooring business. After graduating from Pasadena High School in 1938, McAdoo next enrolled at Pasadena Junior College (now Pasadena College) and it was here that he began taking an interest in architecture and inspiring positive change in the world. During his final year in 1940, he entered a competition to design an architect’s office and living quarters and won second prize. After graduating, he became active at his local Seventh Day Adventist Church giving speeches at meetings of the Youth Crusade for Moral Preparedness and sermons at mass. He then briefly enrolled in the architecture program at University of Southern California in 1941, but withdrew after about a year for financial reasons. To raise money for his education, he went to work for a number of architectural firms in the Los Angeles area.

As World War II continued to escalate, McAdoo joined the US Army Corps of Engineers at Camp Roberts, California in July of 1942. A month later, he married Alice Thelma Dent (1917–2013) and the couple had their first daughter Marcia in 1943. Shortly thereafter, McAdoo left California with his family to Portland, Oregon where he worked in the Kaiser Shipyards designing pipe systems for tankers. While in Portland, McAdoo sent letters of inquiry to University of Oregon and University of Washington. The latter of the two responded more positively and so the McAdoos moved to Seattle, Washington in 1944, which they believed was more racially tolerant than California or Oregon.

While enrolled at University of Washington, McAdoo joined a social group with his fellow architecture students with a shared vision of improving the world through modern design. With this vision, he earned his bachelor’s degree in architecture on June 22, 1946. After graduation, McAdoo worked in the architectural firm of James Joseph Chiarelli (1908–1990) and Paul Hayden Kirk (1914–1995) until April of 1947. During his tenure there, McAdoo became the first African American licensed to practice Architecture in the State of Washington in October 1946. He then went to found his own architectural practice from a makeshift office in the bedroom of his Rainier Vista Housing Project apartment at 4602 Escallonia Court. His first projects were primarily remodels.

To gain name recognition, he submitted a design to the second annual small homes architectural competition whose winners were announced on February 19, 1947.

Although not among the prize winners, the Seattle Times published McAdoo’s design four months later, describing his modest 887-square-foot ranch house with a butterfly roof as “well-suited to the needs of a small family.” He also designed the residence of black dentist and community activist John P. Browning (1904–1957) at 2919 East Howell Street. Over the next two years, McAdoo is only known to have completed two more notable commissions. However, in combination with his earlier designs, they demonstrated his broad interest and skill in varied architectural scales and styles.

Meanwhile, in stark contrast to these large commissions, interest in small “economy homes” was gathering steam across the nation following the recent expansion of the Federal Housing Authority’s home loan program. The movement provided McAdoo the perfect opportunity to pursue his passion for fair housing and to accelerate his career. Concurrently, McAdoo expanded his work into multi-family housing design. From here, the early 1950s continued to be incredibly active both in design work and family life for McAdoo prompting expansion at work and at home. To better house their growing family, the McAdoos purchased a larger home at 2053 24th Avenue East in Seattle’s Montlake neighborhood in September 1952. Despite the racist attempt of neighbors to buy them out, the McAdoos remained in Montlake for three years. During this time, McAdoo returned to larger commissions and earned multiple highlights in local newspapers including Home of the Month in April 1954.

In March of 1955, the McAdoos sold their Montlake home and temporarily relocated the family to a remodeled apartment space above McAdoo’s Capitol Hill office to save money while they planned for their new home. For the next year, they cast a wide net around the City of Seattle in search of a suitable site and eventually focused on Bothell. According to Mrs. McAdoo it appealed to her predilection for suburban living. According to Mr. McAdoo, it fit the bill as an up-and-coming place where an architect could grow with the community and in his own words it ultimately came down to the “friendliness of the people we had met in the community.” On August 31, 1956, they acquired the subject site, a 26,000 square foot parcel in Bothell’s Westhill neighborhood. Over the next year, McAdoo designed his new home and acquired additional land in front of and behind the subject property to maximize leisure and privacy. In doing so, they encountered an exception to their friendly reception. Facing racial prejudice, the McAdoos were only able to acquire the front property through a sympathetic White realtor, business associate, and family friend by the name of Franz Brodine (1908–2002) after the owner refused to sell it to the McAdoos because they were Black.

Between late 1961 and early 1962, the United States Agency for International Development (AID) selected McAdoo to administer a housing program for the Jamaican government, which later gained its independence from the British Empire in August 1962. The job required McAdoo to live in Jamaica full-time for at least a year. Wanting the opportunity to return to their Bothell Home after the program was over, the McAdoos considered leasing it while they were away. However, they ultimately chose to sell it after their realtor insisted that the house would quickly deteriorate if they leased it. So while McAdoo went to Jamaica, his wife oversaw the sale of their home to Clifford P. Johnson (1909–1988), his wife Dorothy L. (1919– 2011), and Dorothy’s sister Freddie Marie Braxton (1924–1993) on March 6, 1962. Mrs. McAdoo, along with her daughter Enid and son Benjamin III (Marcia was in college) left for Jamaica shortly thereafter.

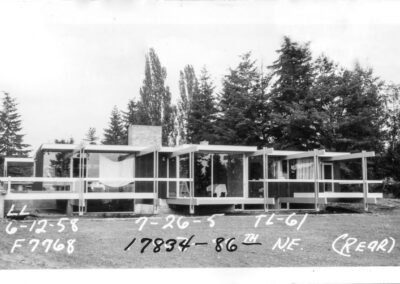

The Building and Site

McAdoo hired building contractor Edwin L. Dahlbeck to construct the house and landscape architects Edward M. Watanabe and Fred Wray to design the surrounding landscape. As built, the McAdoo House was a stunning display in Miesian design. Among its many outstanding features that demonstrate McAdoo’s mastery for design was its use of the site’s existing topography, a first floor elevation that subtly overhangs the exposed basement walls, and a dramatic display of the home’s post and beam frame to create the illusion of building that floats above its foundation. Adding to this dramatic effect were floor to ceiling windows to maximize light, views, and connection to natural space, and delicate bridges with recessed plantings to accentuate the entrances.

McAdoo designed the residence in a Miesian Modernist style, evoking a horizontality of form and a “governance of structure” that can be found in Mies’ emblematic 1951 Farnsworth House. McAdoo utilized Miesian techniques to convey a certain weightlessness of the building envelope, such as large panes of window glazing framed by an articulated grid structure; the use of a flat, built-up roof, supported by large horizontal beams on overhanging eaves in areas where shade is appreciated; and a lack of eaves on those elevations which are purely visual. The residence was built to give an illusion of weightlessness to the structure, which he accomplished through a myriad of techniques. The partial basement was constructed with a footprint that is more diminutive in size than the first floor, and elements of the floor are constructed to extend past the basement wall line. The resulting overhang creates shadows and empty space, which imbue the building with a certain visual weightlessness and disconnection from the ground below. This effect is magnified by rooms on the west and east elevations, which are partially cantilevered to extend further from each elevation; and by the use of elevated bridges to access the primary, east, entrances. Furthermore, the wood posts which support the carport roof terminate approximately three inches above ground and give way to a slender metal pole, creating the effect of a floating post when viewed from afar.

The architect also utilized the natural difference in topography between the east and west portions of the building site to further this illusion, creating a false “moat” with a 10-foot clearing of ground, 4 feet down, which is bounded by a concrete retaining wall and exposed basement walls. Two entrance bridges and a cantilevered first-floor room are positioned to span the “moat” and touch ground at level with the east carport and patio. The negative spaces created between the bridges and cantilevered room are planted with ornamental bamboo and Japanese maple, whose presence accentuate the building’s integration of outdoor and indoor spaces, and further emphasizes the illusion of the building’s weightlessness. Over the course of his career, McAdoo left an imprint on the built environment of the Pacific Northwest as well as the east coast and the international stage, working in a myriad of forms ranging from single family residences, multi-family apartment buildings, and institutions such as churches and educational facilities. The subject property is understood within his larger body of work as a rarified opportunity for McAdoo to pursue a high artistic design for his own enjoyment, and this is evident when compared to his residential designs for other clients. With a few exceptions such as the flat-roofed, Mies-inspired Moorehouse residence in Seattle (1949), McAdoo’s single family residential designs tend to follow the most popular trends of the time which appealed to the average homebuyer. His design philosophy was rooted in balancing an economy of scale with a richness of materials, and much of his portfolio, even the gabled ranch houses, possess a visual horizontality and linearity that places the building in dialogue with its surrounding landscape. The subject property embodies distinctive characteristics of Miesian Modernism and is exemplary of McAdoo’s workmanship in architectural siting and design. The house is also emblematic of the beginning of McAdoo’s architectural and social influence in Bothell, representing a pivotal moment within his productive life as an architect and a tireless advocate for civil rights and access to housing.

The McAdoos had enough space in the rear yard to keep a pet donkey, a gift from McAdoo to his daughter Enid who loved horses and frequently walked to the nearby Evergreen Saddle Club to spend time with them. Mrs. McAdoo also hosted numerous events, concerts, and other activities at their home whose Shoji screens lent themselves well to doubling as stage “curtains” for performances. In addition to hosting performances at their home, the McAdoos also hosted foreign dignitaries. On May 22, 1958, they hosted Daniel Chapman, Ghana’s first Ambassador to the United States since it had recently gained independence the year before. In his company were his wife as well as a press attaché from Ghana’s embassy in Washington D.C and a representative of Washington State Governor Rosellini. The meeting sparked a conversation about potential work opportunities for McAdoo in Ghana including the establishment of a branch office, which led to multiple visits there between 1958 and 1960. However, plans never materialized. Instead McAdoo’s frequent national and international travel introduced the architect to other opportunities abroad.

The Landscape Architect, Edward M. Watanabe (1920-2018)

Edward Makoto Watanabe was born to Japanese immigrants Chiyo and Masahei Watanabe on August 29, 1920, in Seattle, Washington. Watanabe’s father was the owner and operator of the Hotel Victoria at 1211 1st Avenue in Seattle. By 1940, Watanabe was working as a private family gardener and earned an Ornamental Gardening certificate from Edison Technical School (now Seattle Central College) in Seattle, WA the following year. After spending six months incarcerated at the Minidoka prison camp at Hunt, Idaho and being sent to work in Spokane, Washington for a brief period during the first half of WWII, Watanabe enlisted in the US Military in April of 1944. After WWII, Watanabe returned to Seattle where he married Toyoko Hasegawa in August of 1946. The couple then relocated to Corvallis, Oregon where Watanabe enrolled at Oregon State College, now Oregon State University (OSU) in 1948. Recognized on multiple occasions for his exceptional work, Watanabe graduated with a Bachelor of Science from the School of Agriculture in May of 1952. After graduating, Watanabe, his wife, and their son Wayne eventually returned to Seattle where they lived for the remainder of their lives. While here, Watanabe maintained a highly successful career in landscape architecture that spanned multiple decades. He primarily designed landscapes for high-end single-family residences, but also designed landscapes for multi-family, commercial, and institutional buildings—particularly later in his career. In doing so he collaborated with many of the region’s leading architects and won national awards for his work. Aside from the McAdoo House, Watanabe collaborated with McAdoo on the Greenberg Residence (1954) and the Hudesman Residence (1957) both in Seattle’s Seward Park neighborhood.