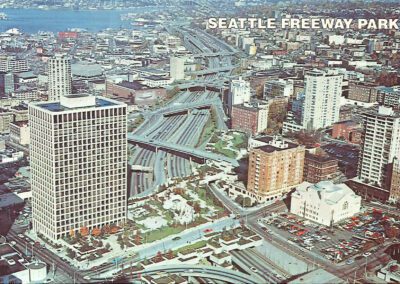

Freeway Park

700 Seneca St.

Built 1976

The source of content for this page is from the Seattle Landmark Nomination Application researched and prepared by Chrisanne Beckner of Historical Research Associates, Inc. Seattle Parks and Recreation, owner of Freeway Park, voluntarily submitted the nomination application.

On July 6, 2022, the Landmarks Preservation Board unanimously designated Freeway Park as a Seattle Landmark. Docomomo US/WEWA supported nomination and designation. Freeway Park was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2019. Designation as a Seattle Landmark will help protect and preserve this iconic park, one of the most significant and unique landscapes in the country.

The History

In 1956, the federal government passed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, offering to fund up to 90 percent of an interconnected network of high-speed roadways. In Washington alone, over 630 construction contracts worth a total of $143 million were awarded over the next two years. Across the United States, freeway projects plowed through existing landscapes, sometimes demolishing historic neighborhoods and town centers. In Seattle, the freeway was designed through dense, urban areas of the city with the intention to capture revenue by pulling people directly into downtown. But, as freeway planning continued, the Seattle public protested envisioning a deep canyon through downtown that would separate residents neighboring communities from the commercial core. In 1961, with protest growing, local architect Paul Thiry joined the First Hill Improvement Club calling for park lids over portions of the freeway. In the local press, the debate for or against focused on practical issues. A lidded freeway, argued proponents, would add to property values and restore connectivity to downtown. Opponents’ argue a park plan would slow freeway construction and add such cost increases that the federal government would likely not agree to continue funding 90 percent of the project. Heated debate raged during meetings between city representatives, state representatives, and the public, but no compromise emerged. Meanwhile, the construction of I-5 moved forward.

Inspired by the 1962 Century 21 Exposition, an ambitious proposal dubbed Forward Thrust, bundled together several popular ideas for Seattle and surrounding King County and proposed to fund them with an array of bond issues paid off through property taxes. In 1968, the first of Forward Thrust capital improvement bond initiatives were approved by voters. Within three years, the King County parks department added 130 new parks, 16 new swimming pools, and doubled the facilities at 55 existing park sites. Perhaps the most famous of the Forward Thrust parks is Freeway Park, the first park to lid an interstate.

The Park

Freeway Park was designed to screen users from the traffic of the surrounding city by leading pedestrians through lushly landscaped spaces with paths and water features constructed of board-formed concrete. Understanding that the park’s urban location would subject most of the plantings to unusual levels of stress, the design relied on hardy species, avoiding more delicate species until they could be planted in combination with mature plants that would provide some shelter. According to the Cultural Landscape Foundation, the park is designed as an “Open Space Sequence” with “three linked outdoor rooms” now known as the Great Box Garden, Central Plaza, and East Plaza.

Along 6th Ave., the Great Box Garden approaches and then wraps around a city park known as Naramore Fountain Park. Completed ten years prior to Freeway Park, the Naramore Fountain was gifted to the city by the architect Floyd A. Naramore, a founding principal of Naramore, Bain, Brady & Johnson (NBBJ). The fountain, designed by artist and University of Washington professor George Tsutakawa, was one of Seattle’s first attempts to soften the edges between the city and the freeway.

North of Seneca St. is Freeway Park’s Central Plaza, which takes up most of a city block and includes many of the park’s character-defining features, including the Canyon and Cascades waterfalls, concrete pathways, as well as concrete benches, planters, and trash receptacles. All these features highlight the distinctive concrete finish with some variations in color and texture. Central Plaza bumps up against the Park Place Building at 1200 6th Ave., which was already in development when the City of Seattle decided to build Freeway Park. In a cooperative agreement, the private developer coordinated the siting of his building with the park design.

To the northeast, accessed by walking under 8th Ave., is Freeway Park’s East Plaza, a peaceful destination located atop the Freeway Park Garage. This plaza has a one-story comfort station with walls of smooth concrete – not the striped or striated with board forms of other park features. The plaza has a staggered, irregularly concrete path between lawns and a tree canopy that creates visual, auditory, and wind screen around its boundary.

The park was an immediate hit both with the local population and the local press, which raved how office workers will stream into it on sunny afternoons. A unique solution to the problem of the urban freeway, the park was praised as an urban oasis.

Lawrence Halprin & Associates

Lawrence Halprin is now heralded as one of the twentieth century’s greatest landscape architects. Collaborating throughout his career with his wife, Anna Halprin, an icon of Modern and Contemporary dance, Halprin was avant-garde in his thinking and driven to unlock people’s innate creativity.

Beginning first with typical postwar projects, including residential gardens, Halprin soon began preparing campus master plans and suburban shopping malls. He developed a reputation as an innovative and collaborative designer and spent much of his career working closely not only with Modern architects but also with dancers like his wife, for whom he designed performance spaces. He is also credited with amplifying the role landscape architects played in urban planning. By the 1970s, Halprin’s firm was an example of how the landscape architecture field was changing to the reuse of underutilized urban spaces.

High-profile successes like Ghirardelli Square and California’s Sea Ranch led to greater creative freedom for Halprin’s team, resulting in much admired landscape features in Portland, Olympia, and Seattle. Like Water Garden in Olympia and the Open Space Sequence in Portland, Freeway Park pairs large dynamic fountains with plants and trees to guide an interactive experience, create interior spaces, and replicate natural forms. At Freeway Park, it is suspended above the ground, held aloft by massive concrete forms. It is not only innovative, but also it is ingenious in its approach to both screening users from the freeway and embracing the freeway so that the park and the freeway cohabitate, collaborating to create a singular experience.

The prime designer orchestrating Halprin’s vision was Angela Danadjieva Tzvetin, After her education and a set design career in Bulgaria, she joined Halprin’s firm in San Francisco in 1965. After leaving Halprin’s firm Danadjieva formed a partnership with Thomas Koenig in California. She was later hired to design two additional landscape projects for Freeway Park: the Paul Pigott Memorial Corridor, constructed in 1984 to connect the park to 9th Ave and the grounds of the Washington State Convention Center in 1988.